Coffee & Sustainability

Coffee is one of the most traded commodities on our planet and provides the livelihood for over 250 million people spread across all continents, countries and religions. Coffee is the fuel of our modern industry, which achieved its breakthrough with industrialisation. It is the elixir of poets and thinkers, the drink of revolutionaries and innovators. It is the companion of cultivated communication and often the catalyst for problem solving.

It has been a globally unifying and equally fiercely contested commodity for centuries, causing much suffering, happiness, poverty and wealth at the same time. In 2020, approximately 170 million bags of green coffee (at 60kg) were produced globally, of which Arabica accounted for 96 million (56%) and Canephora 74 million (43%). Liberica production is still an almost imperceptible 1% of world production and is largely confined to Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines.

20% of the world's coffee production comes from larger farms, 80% from small and micro producers. 80% of the production comes from small and micro producers, some of whom only earn their living in a subsistence economy while helping out on larger farms. Producers often have little knowledge about coffee, its cultivation, species, varieties and processing, let alone an idea of the final beverage and its taste characteristics.

The knowledge about coffee types and varieties is also globally characterised by misinformation. Even people working in the coffee market speak of "Arabica" and "Robusta" - which is wrong. Wine can be divided into red wine and white wine and not into red wine and Riesling. The term "Robusta" in coffee does not botanically refer to a species, but to a variety (i.e. a subdivision of the species). The correct names for the two types of coffee are "Arabica" and "Canephora" - and it should be added that the type is not yet a statement of quality. Even a "100% red wine" is not always good. Incidentally, coffee has a far more complex botanical structure than wine - there are 250 species and over 10,000 varieties - about which we also provide more detailed information in our coffee taxonomy workshop or offer many in the web shop of our sister company "The Coffee Store".

The last few years have brought many changes for coffee producers - most of them to their massive disadvantage. Prices for fertiliser, pesticides, energy and, last but not least, for staff have risen massively..

While production costs rose, the selling prices of coffee fell and interest rates on agricultural loans rose. This is symbolised by the buildings and infrastructures of coffee farms, which are almost impossible to maintain today simply because of the work on the farms - let alone to rebuild. Many stories told by old coffee farmers illustrate the decline in coffee prices. One farmer told how, when he was a little boy, he and his grandfather drove into town with a lorry full of coffee and from the proceeds of the sale of the coffee they could buy a new lorry - when he himself owned the farm, he was able to buy two pairs of jeans for the proceeds of a lorry full of coffee.

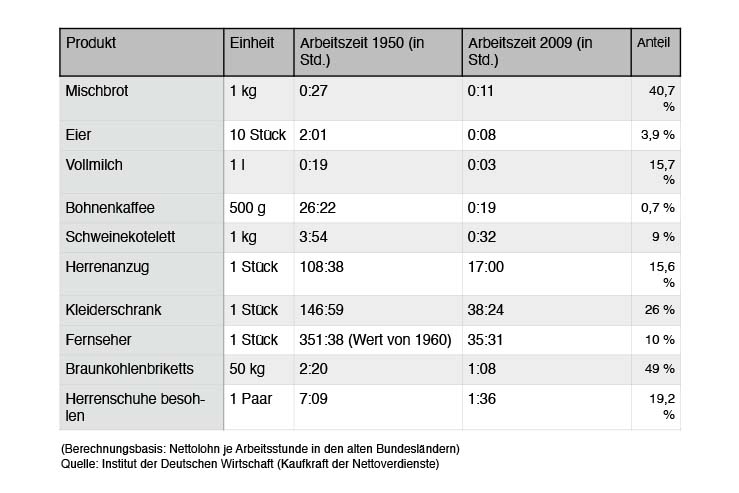

Even here in the consumer countries, the price decline of coffee can be seen dramatically. This can best be seen by comparing the working time of an average paid worker for the purchase of 500g of coffee beans.

Currently, coffee is cheaper than ever before. In 1950, coffee was still unaffordable for most people. At just under €15, a pound of coffee beans was three times as expensive as it is today. For that, however, an average employee had to work 26 hours - today, according to calculations by the IW (Institute of the German Economy), a mere 19 minutes of work are enough. The saving in working hours for beer, on the other hand, is somewhat smaller. For half a litre (price 32 cents at the time), 15 minutes of work were needed in the past - today it takes only three minutes. Coffee today is worth barely 1% of what it was in 1950. No wonder, then, that not only the farmers are in a bad way - the quality of the beans has also deteriorated dramatically. Because the savings have to come from somewhere - and prices for energy, labour, fertiliser, etc. have also risen in the developing countries. Many coffee farmers have therefore already stopped production for many years and either left the country or switched to other products.

Working time in the past and today for selected products.

Coffee production is additionally threatened by climate change. According to the latest estimates, around 70% of the world's arable land will be unsuitable for coffee by 2080. Around 25 million people will thus lose their source of income, and refugee flows to the USA of unimagined size could form in Latin American countries. What prospects do the prices and cultivation situations offer for coffee pickers in these countries?

Coffee pests, on the other hand, are benefiting from climate change. According to estimates by the ICO (International Coffee Organisation), coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix) (a fungus that attacks the leaves and causes them to die) already caused global damage of around US$ 550 million in 2015 and is also spreading increasingly in altitudes that were previously free of infestation. The Broca beetle (Hypothenemus hampei), which is spreading more in East African countries, has caused damage of around US$ 500 million there, according to estimates by the FAO (Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations). A new subspecies causes a taste of rotten potatoes when it attacks, making entire harvests unsaleable.

The combination of economic (poor selling prices for green coffee, rising costs of coffee cultivation) and environmental (lack of rain or excessive rainfall) factors are leading to a dramatic decline in the production of coffee.

India can be considered an iconic example of this. Since 2015, there have been massive crop failures of up to 50% of the average yield in some cases. Major drought is followed by massive rain events that erode the fertile surface layers of the soil, cause buildings and roads to collapse and give way to massive drought again after a short time. The coffee plants are initially able to compensate for their weakening through the crop losses, but die after two to three years of repeated situations.

At the same time, global coffee consumption is increasing, especially in emerging countries such as Brazil, India and Mexico.

So coffee will become a luxury product again - and that's a good thing. Because things could not be any less sustainable in the coffee industry. This also shows the downright hypocritical cover-up and reassurance function of the numerous certificates that certify such situations as "fair" and thus become the moral fig leaf of the profiteers in the market and vehicle for the consumer who is taken for a fool with their help. The consumer only has the chance to find out from his seller or roaster about the trade route and the hopefully existing personal relationships with the producers and not to be fobbed off and blinded solely by certificates or individual figures such as FOB prices (which are completely meaningless for the farmer's price).

In the future, we will only be able to drink coffee if it is worthwhile for the producers to grow coffee and thus ensure a sustainable income. Likewise, there must be prospects for the coffee pickers and their children to be able to educate and train themselves in order to have better job prospects.

It must be worthwhile for the farms to live and work in harmony with nature in real terms - for this, education must be provided on the relationships between microclimates, insolation, hydrology, soil science (microbiomes), allelopathy (shade plants, ground cover, ...), and the correct cultivation and processing of coffee.

Coffee farms need to become more resilient to climate events, more shade trees need to be planted, which initially reduce the crop yield, but stabilise it and improve the quality and taste of the coffee. Targeted planting of ground covers can store more water supplies and secure soils against erosion by rain.

By growing coffee varieties better adapted to local conditions and evolving fermentation styles, farms can generate better revenues through higher quality coffee and more unique flavour profiles. In the event of a global coffee crisis, the industry would also be better protected through broader genetics.

The use of coffee by-products such as coffee cherries, coffee leaves or coffee wood could enable coffee farmers to generate additional income - a prerequisite for this is access to the markets, which is currently massively hampered by regulations such as the Novel Food Regulation. Here, it would make sense for a consortium of coffee companies to jointly form and advocate for the use and legal paving of the way for the consumption of these products - also for the benefit of the farmers..

As a first step, consumers can try to buy coffee not according to certificates, but according to long-standing direct contacts with coffee farmers and unique taste profiles. The rule is: coffee produced under good conditions also tastes good! Certificates only help those who issue them. A little more honesty and critical examination of advertising claims is essential and the most important step for consumers to help coffee farmers.